In the year 1927 we were playing jazz in a speak-easy just south of Morgan, Illinois, a town seventy miles from Chicago. It was real hick country, not another big town for twenty miles in any direction. But there were a lot of farm boys with a hankering for something stronger than Moxie after a hot day in the field, and a lot of would-be jazz-babies out stepping with their drugstore-cowboy boyfriends. There were also some married men (you always know them, friend; they might as well be wearing signs) coming far out of their way to be where no one would recognize them while they cut a rug with their not-quite-legit lassies.

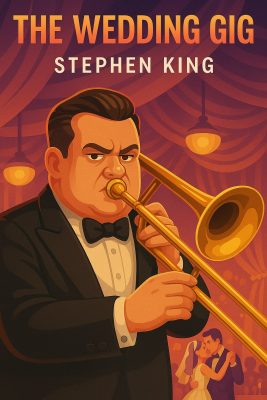

That was when jazz was jazz, not noise. We had a five-man combination — drums, cornet, trombone, piano, trumpet — and we were pretty good. That was still three years before we made our first record and four years before talkies.

We were playing “Bamboo Bay” when this big fellow walked in, wearing a white suit and smoking a pipe with more squiggles in it than a French horn. The whole band was a little tight by that time but everyone in the crowd was absolutely blind and really ramping the joint. They were in a good mood, though; there hadn’t been a single fight all night. All of us guys were sweating rivers and Tommy Englander, the guy who ran the place, kept sending up rye as smooth as a varnished plank. Englander was a good joe to work for, and he liked our sound. Of course that made him aces in my book.

The guy in the white suit sat down at the bar and I forgot him. We finished up the set with “Aunt Hagar’s Blues,” which was a tune that passed for racy out in the boondocks back then, and got a good round of applause. Manny had a big grin on his face when he put his trumpet down, and I clapped him on the back as we left the bandstand. There was a lonely-looking girl in a green evening gown who had been giving me the eye all night. She was a redhead, and I’ve always been partial to those. I got a signal from her eyes and the tilt of her head, so I started weaving through the crowd to see if she wanted a drink.

I was halfway there when the man in the white suit stepped in front of me. Up close he looked like a pretty tough egg. His hair was bristling up in the back in spite of what smelled like a whole bottle of Wildroot Creme Oil and he had the flat, oddly shiny eyes that some deep-sea fish have. “Want to talk to you outside,” he said. The redhead looked away with a small pout. “It can wait,” I said. “Let me by.” “My name is Scollay. Mike Scollay.” I knew the name. Mike Scollay was a small-time racketeer from Shytown who paid for his beer and skittles by running booze in from Canada. The high-tension stuff that started out where the men wear skirts and play bagpipes. When they aren’t tending the vats, that is. His picture had been in the paper a few times. The last time had been when some other dancehall Dan tried to gun him down.

“You’re pretty far from Chicago, my friend,” I said. “I brought some chaperones,” he said, “don’t worry. Outside.”

The redhead took another look. I pointed at Scollay and shrugged. She sniffed and turned her back. “There,” I said. “You queered that.” “Bimbos like that are a penny a bushel in Chi,” he said. “I didn’t want a bushel.” “Outside.”

I followed him out. The air was cool on my skin after the smoky atmosphere of the club, sweet with fresh-cut alfalfa. The stars were out, soft and flickering. The hoods were out, too, but they didn’t look soft, and the only things flickering were their cigarettes.

“I got a job for you,” Scollay said.

“Is that so.”

“Pays two C’s. Split it with the band or hold back hundred for yourself.”

“What is it?”

“A gig, what else? My sis is tying the knot. I want you to play for the reception. She likes Dixieland. Two of my boys say you play good Dixieland.”

I told you Englander was good to work for. He was paying ins eighty bucks a week. This guy was offering over twice that for one gig.

“It’s from five to eight, next Friday,” Scollay said. “At Che Sons of Erin Hall on Graver Street.”

“It’s too much,” I said. “How come?”

“There’s two reasons,” Scollay said. He puffed on his pipe. It looked out of place in the middle of that yegg’s face. He should have had a Lucky Strike Green dangling from that mouth, or maybe a Sweet Caporal. The Cigarette of Bums. With the pipe he didn’t look like a bum. The pipe made him look sad and funny.

“Two reasons,” he repeated. “Maybe you heard the Greek tried to rub me out.”

“I saw your picture in the paper,” I said. “You were the guy trying to crawl into the sidewalk.”

“Smart guy,” he growled, but with no real force. “I’m getting too big for him. The Greek is getting old. He thinks small. He ought to be back in the old country, drinking olive oil and looking at the Pacific.”

“I think it’s the Aegean,” I said.

“I don’t give a tin shit if it’s Lake Huron,” he said. “Point is, he don’t want to be old. He still wants to get me. He don’t know the coming thing when he sees it.”

“That’s you.”

“You’re fucking-A.”

“In other words, you’re paying two C’s because our last number might be arranged for Enfield rifle accompaniment. ‘

Anger flashed in his face, but there was something else there, as well. I didn’t know what it was then, but I think I do mow. I think it was sorrow. “Buddy Gee, I got the best protection money can buy. If anyone funny sticks his nose in, he won’t get a chance to sniff twice.” “What’s the other thing?”

He spoke softly. “My sister’s marrying an Italian.” “A good Catholic like you,” I sneered softly. The anger flashed again, white-hot, and for a minute I thought I’d pushed him too far. “A good mick! A good old shanty-Irish mick. Sonny, and you better not forget it!” To that he added, almost too low to be heard, “Even if I did lose most of my hair, it was red.”

I started to say something, but he didn’t give me the chance. He swung me around and pressed his face down until our noses almost touched. I have never seen such anger and humiliation and rage and determination in a man’s face. You never see that look on a white face these days, how it is to be hurt and made to feel small. All that love and hate. But I saw it on his face that night and knew I could crack wise a few more times and get my ass killed.

“She’s fat,” he half-whispered, and I could smell checker-berry mints on his breath. “A lot of people have been laughing at me while my back was turned. They don’t do it when 1 can see them, though, I’ll tell you that, Mr. Cornet Player. Because maybe this dago was all she could get. But you’re not gonna laugh at me or her or the dago. And nobody else is, either. Because you’re gonna play too loud. No one is going to laugh at my sis.”

“We never laugh when we play our gigs. Makes it too hard to pucker.”

That relieved the tension. He laughed — a short, barking laugh. “You be there, ready to play at five. The Sons of Erin on Grover Street. I’ll pay your expenses both ways, too.”

He wasn’t asking. I felt railroaded into the decision, but he wasn’t giving me time to talk it over. He was already striding away, and one of his chaperones was holding open the back door of a Packard coupe.

They drove away. I stayed out awhile longer and had a smoke. The evening was soft and fine and Scollay seemed more and more like something I might have dreamed. I was just wishing we could bring the bandstand out to the parking lot and play when Biff tapped me on the shoulder. “Time,” he said. “Okay.”

We went back in. The redhead had picked up some salt-and-pepper sailor who looked twice her age. I don’t know what a member of the U.S. Navy was doing in Illinois, but as far as I was concerned, she could have him if her taste was that bad. I didn’t feel so good. The rye had gone to my head, and Scollay seemed a lot more real in here, where the fumes of what he and his kind sold were strong enough to float on.

“We had a request for ‘Camptown Races,’ ” Charlie said.

“Forget it,” I said curtly. “We don’t play that nigger stuff till after midn

ight.”

I could see Billy-Boy stiffen as he was sitting down to the piano, and then his face was smooth again. I could have kicked myself around the.block, but, goddammit, a man can’t shift gears on his mouth overnight, or in a year, or maybe even in ten. In those days nigger was a word I hated and kept saying.

I went over to him. “I’m sorry, Bill — I haven’t been myself tonight.”

“Sure,” he said, but his eyes looked over my shoulder and I knew my apology wasn’t accepted. That was bad, but I’ll tell you what was worse — knowing he was disappointed in me.

I told them about the gig during our next break, being square with them about the money and how Scollay was a hoodlum (although I didn’t tell them about the other hood who was out to get him). I also told them that Scollay’s sister was fat and Scollay was sensitive about it. Anyone who cracked any jokes about inland barges might wind up with a third breather-hole, somewhat above the other two.

I kept looking at Billy-Boy Williams while I talked, but you could read nothing on the cat’s face. It would be easier trying to figure out what a walnut was thinking by reading the wrinkles on the shell. Billy-Boy was the best piano player we ever had, and we were all sorry about the little ways it got taken out on him as we traveled from one place to another. In the south was the worst, of course — Jim Crow car, nigger heaven at the movies, stuff like that — but it wasn’t that great in the north, either. But what could I do? Huh? You go on and tell me. In those days you lived with those differences.

We turned up at the Sons of Erin Hall on Friday at four o’clock, an hour before. We drove up in the special Ford truck Biff and Manny and me put together. The back end was all enclosed with canvas, and there were two cots bolted on the floor. We even had an electric hotplate that ran off the battery, and the band’s name was painted on the outside.

The day was just right — a ham-and-egger if you ever saw one, with little white summer clouds casting shadows on the fields. But once we got into the city it was hot and kind of grim, full of the hustle and bustle you got out of touch with in a place like Morgan. By the time we got to the hall my clothes were’sticking to me and I needed to visit the comfort station. I could have used a shot of Tommy Englander’s rye, too.

The Sons of Erin was a big wooden building, affiliated with the church where Scollay’s sis was getting married. You know the sort of place I mean if you ever took the Wafer, 1 guess — CYO meetings on Tuesdays, bingo on Wednesdays, and a sociable for the kids on Saturday nights.

We trooped up the walk, each of us carrying his instrument in one hand and some part of Biff’s drum-kit in the other. A thin lady with no breastworks to speak of was directing traffic inside. Two sweating men were hanging crepe paper. There was a bandstand at the front of the hall, and over it was a banner and a couple of big pink paper wedding bells. The tinsel lettering on the banner said best always maureen and rico.

Maureen and Rico. Damned if I couldn’t see why Scollay was so wound up. Maureen and Rico. Stone the crows.

The thin lady swooped down on us. She looked like she had a lot to say so I beat her to punch. “We’re the band,” I said.

“The band?” She blinked at our instruments distrustfully. “Oh. I was hoping you were the caterers.”

I smiled as if caterers always carried snare drums and trombone cases.

“You can — ” she began, but just then a ruff-tuff-creampuff of about nineteen strolled over. A cigarette was dangling from the comer of his mouth, but so far as I could see it wasn’t doing a thing for his image except making his left eye water. “Open that shit up,” he said.

Charlie and Biff looked at me. I shrugged. We opened our cases and he looked at the horns. Seeing nothing that looked like you could load it and fire it, he wandered back to his comer and sat down on a folding chair.

“You can set your things up right away,” the thin lady went on, as if she had never been interrupted. “There’s a piano in the other room. I’ll have my men wheel it in when we’re done putting up our decorations.”

Biff was already lugging his drum-kit up on to the little stage.

“I thought you were the caterers,” she repeated in a distraught way. “Mr. Scollay ordered a wedding cake and there are hors d’oeuvres and roasts of beef and — “

“They’ll be here, ma’am,” I said. “They get payment on delivery.”

” — two roasts of pork and a capon and Mr. Scollay will be just furious if — ” She saw one of her men pausing to light a cigarette just below a dangling streamer of crepe and shrieked, “HENRY!” The man jumped as if he had been shot. I escaped to the bandstand.

We were all set up by a quarter of five. Charlie, the trombone player, was wah-wahing away into a mute and Biff was loosening up his wrists. The caterers had arrived at 4:20 and Miss Gibson (that was the thin lady’s name; she made a business out of such affairs) almost threw herself on them.

Four long tables had been set up and covered with white linen, and four black women in caps and aprons were setting places. The cake had been wheeled into the middle of the room for everyone to gasp over. It was six layers high, with a little bride and groom standing on top.

I walked outside to grab a fag and just about halfway through it I heard them coming — tooting away and raising a racket. I stayed where I was until I saw the lead car coming around the corner of the block below the church, then I snubbed my smoke and went inside.

“They’re coming,” I told Miss Gibson.

She went white and actually swayed on her heels. There was a lady that should have taken up a different profession — interior decoration, maybe, or library science. “The tomato juice!” she screamed. “Bring in the tomato juice!”

I went back to the bandstand and we got ready. We had played gigs like this before — what combo hasn’t? — and when the doors opened, we swung into a ragtime version of “The Wedding March” that I had arranged myself. If you think that sounds sort of like a lemonade cocktail I have to agree with you, but most receptions we played for just ate it up, and this one was no different. Everybody clapped and yelled and whistled, then started gassing amongst themselves. But I could tell by the way some of them were tapping their feet while they talked that we were getting through. We were on — I thought it was going to be a good gig. I know everything they say about the Irish, and most of it’s true, but, hot damn! they can’t not have a good time once they are set up for it.

All the same, I have to admit I almost blew the whole number when the groom and the blushing bride walked in. Scollay, dressed in a morning coat and striped trousers, shot me a hard look, and don’t think I didn’t see it. I managed to keep a poker face, and the rest of the band did, too — no one so much as missed a note. Lucky for us. The wedding party, which looked as if it were made up almost entirely of Scollay’s goons and their molls, were wise already. They had to be, if they’d been at the church. But I’d only heard faint rumblings, you might say.

You’ve heard about Jack Sprat and his wife. Well, this was a hundred times worse. Scollay’s sister had the red hair he was losing, and it was long and curly. But not that pretty auburn shade you may be imagining. No, this was County Cork red — bright as a carrot and kinky as a bedspring. Her natural complexion was curd-white but she was wearing almost too many freckles to tell. And had Scollay said she was fat? Brother, that was like saying you could buy a few things in Macy’s. She was a human dinosaur — three hundred and fifty pounds if she was one. It had all gone to her bosom and hips and butt and thighs, like it usually does on fat girls, making what should be sexy grotesque and sort of frightening instead. Some fat girls have pathetically pretty faces, but Scollay’s sis didn’t even have that. Her eyes were too close together, her mouth was too big, and she had jug-ears. Then there were the freckles. Even thin she would have been ugly enough to stop a clock — hell, a whole show-window of them.

That alone wouldn’t have made anybody laugh, unless they were stupid or just poison-mean. It was when you added the groom, Rico, to the picture that you wanted to laugh until you cried. He could have put on a top hat and still stood in the top half of her shadow. He looked like he m

ight have weighed ninety pounds or so, soaking wet. He was skinny as a rail, his complexion darkly olive. When he grinned around nervously, his teeth looked like a picket fence in a slum neighborhood.

We kept right on playing.

Scollay roared: “The bride and the groom! God give ’em every happiness!” And if God don’t, his thundering brow proclaimed, you folks here better — at least today.

Everyone shouted their approval and applauded. We finished our number with a flourish, and that brought another round. Scollay’s sister Maureen smiled. God, her mouth was big. Rico simpered.

For a while everyone just walked around, eating cheese and cold cuts on crackers and drinking Scollay’s best bootleg Scotch. I had three shots myself between numbers, and it put Tommy Englander’s rye in the shade.

Scollay began to look happier, too — a little, anyway.

He cruised by the bandstand once and said, “You guys play pretty good.” Coming from a music lover like him, I reckoned that was a real compliment.

Just before everyone sat down to the meal, Maureen came up herself. She was even uglier up close, and her white gown (there must have been enough white satin wrapped around that mama to cover three beds) wasn’t helping her at all. She asked us if we could play “Roses of Picardy” like Red Nichols and His Five Pennies, because, she said, it was her very favorite song. Fat and ugly she was, but hoity-toity she was not — unlike some of the two-bitters who’d been dropping by to make requests. We played it, but not very well. Still, she gave us a sweet smile that was almost enough to make her pretty, and she applauded when it was done.

They sat down to dinner around 6:15, and Miss Gibson’s hired help rolled the chow to them. They fell to like a bunch of animals, which was not entirely surprising, and kept knocking back that high-tension booze the whole time. I couldn’t help watching the way Maureen was eating. I tried to look away, but my eye kept wandering back, as if to make sure it was seeing what it thought it was seeing. The rest of them were packing it in, but she made them look like old ladies in a tearoom. She had no more time for sweet smiles or listening to “Roses of Picardy”; you could have stuck a sign in front of her that said woman working That lady didn’t need a knife and fork; she needed a steam shovel and a conveyor belt. It was sad to watch her. And Rico (you could just see his chin over the table where the bride was sitting, and a pair of brown eyes as shy as a deer’s) kept handing her things, never changing that nervous simper.

We took a twenty-minute break while the cake-cutting ceremony was going on, and Miss Gibson herself fed us in the kitchen. It was hot as blazes with the cookstove on, and none of us was too hungry. The gig had started out feeling right and now it felt wrong. I could see it on my band’s faces… on Miss Gibson’s, too, for that matter.

By the time we returned to the bandstand, the drinking had begun in earnest. Tough-looking guys staggered around with silly grins on their mugs or stood in corners haggling over racing forms. Some couples wanted to Charleston, so we played “Aunt Hagar’s Blues” (those goons ate it up) and “I’m Gonna Charleston Back to Charleston” and some other numbers like that. Jazz-baby stuff. The debs rocked around the floor, flashing their rolled hose and shaking their fingers beside their faces and yelling voe-doe-dee-oh-doe, a phrase that makes me feel like sicking up my supper to this very day. It was getting dark out. The screens had fallen off some of the windows and moths came in and flitted around the light fixtures in clouds. And, as the song says, the band played on. The bride and groom stood on the sidelines — neither of them seemed interested in slipping away early — almost completely neglected. Even Scollay seemed to have forgotten about them. He was pretty drunk.

It was almost 8:00 when the little fellow crept in. I spotted him immediately because he was sober and he looked scared; scared as a nearsighted cat in a dog pound. He walked up to Scollay, who was talking with some floozie right by the bandstand, and tapped him on the shoulder. Scollay wheeled around, and I heard every word they said. Believe me, I wish I hadn’t.

“Who the hell are you?” Scollay asked rudely.

“My name is Demetrius,” the fellow said. “Demetrius Katzenos. I come from the Greek.”

Motion on the floor came to a dead stop. Jacket buttons were freed, and hands stole out of sight under lapels. I saw Manny looking nervous. Hell, I didn’t feel so calm myself. We kept on playing though, you bet.

“Is that right,” Scollay said quietly, almost reflectively.

The guy burst out, “I didn’t want to come, Mr. Scollay! The Greek, he has my wife. He say he kill her if I doan give you his message!”

“What message?” Scollay growled. The thunderclouds were back on his forehead.

“He say — ” The guy paused with an agonized expression. His throat worked as if the words were physical things, caught in there and choking him. “He say to tell you your sister is one fat pig. He say… he say…” His eyes rolled wildly at Scollay’s still expression. I shot a look at Maureen. She looked as if she had been slapped. “He say she got an itch. He say if a fat woman got an itch on her back, she buy a back-scratcher. He say if a woman got an itch in her parts, she buy a man.”

Maureen gave a great strangled cry and ran out, weeping. The floor shook. Rico pattered after her, his face bewildered. He was wringing his hands.

Scollay had grown so red his cheeks were actually purple. I half-expected — maybe more than half-expected — his brains to just blow out his ears. I saw that same look of mad agony I had seen in the dark outside Englander’s. Maybe he was just a cheap hood, but I felt sorry for him. You would have, too.

When he spoke his voice was very quiet — almost mild.

“Is there more?”

The little Greek man quailed. His voice was splintery with anguish. “Please doan kill me, Mr. Scollay! My wife — the Greek, he got my wife! I doan want to say these thing! He got my wife, my woman — “

“I ain’t going to hurt you,” Scollay said, quieter still. “Just tell me the rest.”

“He say the whole town laughing at you.”

We had stopped playing and there was dead silence for a second. Then Scollay turned his eyes to the ceiling. Both of his hands were shaking and held out clenched in front of him. He was holding them in fists so tight that it seemed I could see his hamstrings standing out right through his shirt.

“ALL RIGHT!” he screamed. “ALL RIGHT!”

He broke for the door. Two of his men tried to stop him, tried to tell him it was suicide, just what the Greek wanted, but Scollay was like a crazy man. He knocked them down and rushed out into the black summer night.

In the dead quiet that followed, all I could hear was the messenger’s tortured breathing and somewhere out back, the soft sobbing of the bride.

Just about then the young kid who had braced us when we came in uttered a curse and made for the door. He was the only one.

Before he could even get under the big paper shamrock hung in the foyer, automobile tires screeched on the pavement and engines revved up — a lot of engines. It sounded like Memorial Day at the Brickyard out there.

“Oh dear-to-Jaysus!” the kid screamed from the doorway. “It’s a fucking caravan! Get down, boss! Get down! Get down — ”

The night exploded with gunfire. It was like World War I out there for maybe a minute, maybe two. Bullets stitched across the open door of the hall, and one of the hanging light-globes overhead exploded. Outside the night was bright with Winchester fireworks. Then the cars howled away. One of the molls was brushing broken glass out of her bobbed hair.

Now that the danger was over, the rest of the goons rushed out. The door to the kitchen banged open and Maureen ran through again. Everything she had was jiggling. Her face was more puffy than ever. Rico came in her wake like a bewildered valet. They went out the door.

Miss Gibson appeared in the empty hall, her eyes wide and shocked. The little man who had started all the trouble with his singing telegram had powdered.

“It was shooting,” Miss Gibson murmured. “What happened?”

“I think the Greek just cooled the paymaster,” Biff said. She looked at me, bewildered, but before I could translate Billy-Boy said in his soft, polite voice: “He means that Mr. Scollay just got rubbed out, Miz Gibson.”

Miss Gibson stared at him, her eyes getting wider and wider, and then she fainted dead away. I felt a little like fainting myself.

Just then, from outside, came the most anguished scream I have ever heard, then or since. That unholy caterwauling just went on and on. You didn’t have to peek out the door to know who was tearing her heart out in the street, keening over her dead brother even while the cops and newshawks were on their way.

“Let’s blow,” I muttered. “Quick.”

We had it packed in before five minutes had passed. Some of the goons came back inside, but they were too drunk and too scared to notice the likes of us.

We went out the back, each of us carrying part of Biffs drum-kit. Quite a parade we must have made, walking up the street, for anyone who saw us. I led the way with my horn case tucked under my arm and a cymbal in each hand. The boys stood on the corner at the end of the block while I went back for the truck. The cops hadn’t shown yet. The big girl was still crouched over the body of her brother in the middle of the street, wailing like a banshee while her tiny groom ran around her like a moon orbiting a big planet.

I drove down to the corner and the boys threw everything in the back, willy-nilly. Then we hauled ass out of there. We averaged forty-five miles an hour all the way back to Morgan, back roads or not, and either Scollay’s goons must never have bothered to tip the cops to us, or else the cops didn’t care, because we never heard from them.

We never got the two hundred bucks, either.

She came into Tommy Englander’s about ten days later, a fat Irish girl in a black mourning dress. The black didn’t look any better than the white satin.

Englander must have known who she was (her picture had been in the Chicago papers, next to Scollay’s) because he showed her to a table himself and shushed a couple of drunks at the bar who had been snickering at her.

I felt badly for her, like I feel for Billy-Boy sometimes. It’s tough to be on the outside. You don’t have to be out there to know, although I’d have to agree that you can’t know just what it’s like. And she had been very sweet, the little I had talked to her.

When the break came, I went over to her table.

“I’m sorry about your brother,” I said awkwardly. “I know he really cared for you, and — “

“I might as well have fired those guns

myself,” she said. She was looking down at her hands, and now that I noticed them I saw that they were really her best feature, small and comely. “Everything that little man said was true.”

“Oh, say now,” I replied — a non sequitur if ever there was one, but what else was there to say? I was sorry I’d come over, she talked so strangely. As if she was all alone, and crazy.

“I’m not going to divorce him, though,” she went on. “I’d kill myself first, and damn my soul to hell.”

“Don’t talk that way,” I said.

“Haven’t you ever wanted to kill yourself?” she asked, looking at me passionately. “Doesn’t it make you feel like that when people use ‘you badly and then laugh at you? Or did no one ever do it to you? You may say so, but you’ll pardon me if I don’t believe it. Do you know what it feels like to eat and eat and hate yourself for it and then eat more? Do you know what it feels like to kill your own brother because you are fat?”

People were turning to look, and the drunks were sniggering again.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

I wanted to tell her I was sorry, too. I wanted to tell her… oh, anything at all, I reckon, that would make her feel better. Holler down to where she was, inside all that flab. But I couldn’t think of a single thing.

So I just said, “I have to go. We have to play another set.”

“Of course,” she said softly. “Of course you must… or they’ll start to laugh at you. But why I came was — will you play ‘Roses of Picardy’? I thought you played it very nicely at the reception. Will you do that?”

“Sure,” I said. “Be glad to.”

And we did. But she left halfway through the number, and since it was sort of schmaltzy for a place like Englander’s, we dropped it and swung into a ragtime version of “The Varsity Drag.” That one always tore them up. I drank too much the rest of the evening and by closing I had forgotten all about her. Well, almost.

Leaving for the night, it came to me. What I should have told her. Life goes on — that’s what I should have said. That’s what you say to people when a loved one dies. But, thinking it over, I was glad I didn’t. Because maybe that was what she was afraid of.

* * * * *

Of course now everyone knows about Maureen Romano and her husband Rico, who survives her as the taxpayers’ guest in the Illinois State Penitentiary. How she took over Scollay’s two-bit organization and turned it into a Prohibition empire that rivaled Capone’s. How she wiped out two other North Side gang leaders and swallowed their operations. How she had the Greek brought before her and supposedly killed him by sticking a piece of piano wire through his left eye and into his brain as he knelt in front of her, blubbering and pleading for his life. Rico, the bewildered valet, became her first lieutenant, and was responsible for a dozen gangland hits himself.

I followed Maureen’s exploits from the West Coast, where we were making some pretty successful records. Without Billy-Boy, though. He formed a band of his own not long after we left Englander’s, an all-black combination that played Dixieland and ragtime. They did real well down south, and 1 was glad for them. It was just as well. Lots of places wouldn’t even audition us with a Negro in the group.

But I was telling you about Maureen. She made great news copy, and not just because she was a kind of Ma Barker with brains, although that was part of it. She was awful big and she was awful bad, and Americans from coast to coast felt a strange sort of affection for her. When she died of a heart attack in 1933, some of the papers said she weighed five hundred pounds. 1 doubt it, though. No one gets that big, do they?

Anyway, her funeral made the front pages. It was more than you could say for her brother, who never got past page four in his whole miserable career. It took ten pallbearers to carry her coffin. There was a picture of them toting it in one of the tabloids. It was a horrible picture to look at. Her coffin was the size of a meat locker — which, in a way, I suppose it was.

Rico wasn’t bright enough to hold things together by himself, and he fell for assault with intent to kill the very next year.

I’ve never been able to get her out of my mind, or the agonized, hangdog way Scollay had looked that first night when he talked about her. But I cannot feel too sorry for her, looking back. Fat people can always stop eating. Guys like Billy-Boy Williams can only stop breathing. I still don’t see any way I could have helped either of them, but I do feel sort of bad every now and then. Probably just because I’ve gotten a lot older and don’t sleep as well as I did when I was a kid. That’s all it is, isn’t it? Isn’t it?

December 1980